The hidden passageways of Lübeck

Behind the pretty brick gables of Lübeck’s houses lie hidden worlds which appear charming to us now, but were once home to the city’s poorest inhabitants

A global pandemic followed by cancelled flights meant that I’d been away from Germany for nearly five years when I touched down in Hamburg in May 2024. I’d been to Hamburg before, but this time I wanted to visit nearby Lübeck, a city I’d never previously visited.

I’d wanted to visit Lübeck ever since watching Jonathan Meades’ TV programme Magnetic North in 2008. I was studying for my PhD in German art history at the time, so Magnetic North, in which Meades explored the cultures of northern Europe’s Baltic states, came along at the perfect time.1 In retrospect, it’s difficult to understate just how influential Meades’ programme was for me. It opened my eyes to a vision of Europe that I’d not encountered before, challenging the assumption that Mediterranean culture—its food, its art, its architecture—was somehow superior to what was produced around the shores of that other great European sea to the north.

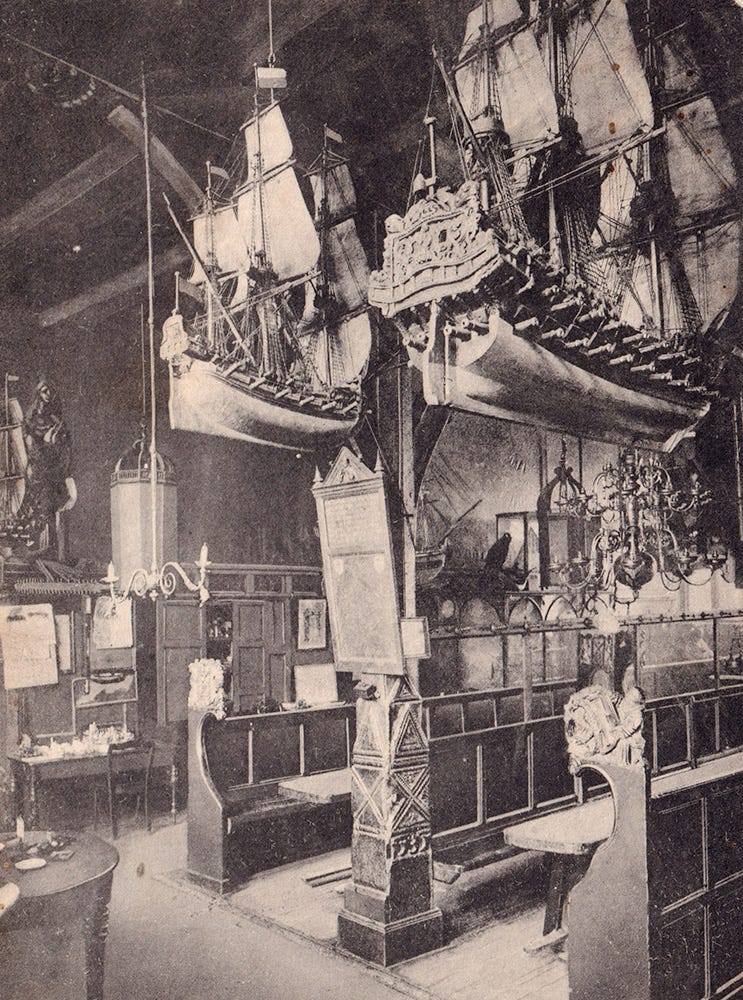

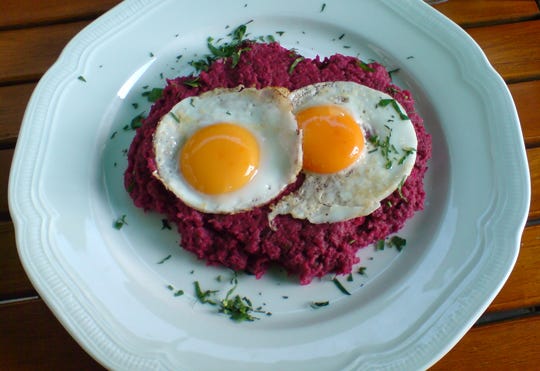

Of all the places Meades visited I was most curious about Lübeck, not least because of the Schiffergesellschaft, the old shipping guild—now a restaurant—from whose ceiling model sailing ships hang. And of course Labskaus, a dish so thoroughly enmeshed into the culture and history of the region, in spite of it looking like something the Dentrassis might serve up on a Vogon Constructor Fleet.2

Happily, Lübeck did not disappoint, and around every corner I encountered a new delight. A gently curving street of medieval houses with their brick façades and stepped gables. Or a stunning vista towards one of the city’s towering, steepled churches. Then there were the city’s surviving gates, the Holstentor and the Burgtor. And, at the edges of the old city, timber-framed cottages overlooking the canal; a sense that wouldn’t have looked out of place in an English Cotswolds village.

The Streets are very fair and adorn’d with divers magnificent Buildings (The Compleat Geographer, 1723)

Medieval Lübeck

Lübeck’s present-day greatness comes from having been one of the most important cities of the Hanseatic League, a maritime trading network that stretched across northern Europe, from London in the west to Novgorod in the east, between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries. The origins of the medieval city go back to 1159, when the Duke of Bavaria and Saxony, Henry the Third (also known as Henry the Lion) ordered the city’s reconstruction after it was destroyed in a fire in 1157. Lübeck’s importance as a trading centre was boosted when the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick the Second, made it an imperial free city in 1226. By the middle of the fourteenth century Lübeck had a population of around 20,000 inhabitants. The Reformation also had a significant impact on Lübeck, which became an important Lutheran city in the sixteenth century. The city’s five main churches are examplars of medieval brick-built architecture, and their combined seven spires mean that Lübeck has more church towers over 100 metres in height than anywhere else in the world. With its churches, town hall, gates, and scores of brick-built merchants’ and guildhouses, Lübeck is a stunning symphony of medieval brick architecture.

Lübeck’s hidden passageways

All of which alone make Lübeck worth visiting, but there was one other side to the city that I hadn’t been aware of, and could have easily overlooked, had my sense of curiosity not got the better of me. In and around the side streets of the city were passageways (Gänge) leading off the street, like portals to other worlds. It was not clear at first whether public entry into these passageways was permitted, and I did encounter one or two that had signs explicitly stating that entry was forbidden. But eventually I hesitantly made my way into one, where I encountered a small courtyard garden, with a number of front doors to houses, and another connected passageway that brought me back out onto an adjacent street. Now I realised that each of these passageways had names and street numbers, and I felt emboldened enough to explore more of them.

And the more I looked, the more I found. Most led to small courtyard gardens and interior spaces, others to childrens’ play areas, to larger gardens, or simply to other passageways connecting to other streets. They exist in an ambiguous semi-public, semi-private realm, where neighbours, friends and families might stand and chat or sit down together for an al-fresco meal, and where they might find themselves imposed upon by the occasional apologetic tourist. They thread in and out of the street blocks, joining up with each other in much the same way that the glass-covered passages once did in pre-Hausmannian Paris.

The variety of these spaces were fascinating. They had an organic nature, and I had the sense that rather than being planned spaces, they were merely a kind of negative space, formed by the external walls of clusters of houses. They are unlike the interior courtyards (Hinterhöfe) that you find in nineteenth-century tenement blocks in modern German towns and cities, and more reminiscent of the alleyways (sikkak) that connect neighbourhoods (furuwq) in historic Arabic settlements.

The origins of Lübeck’s hidden passageways

As the primary city of the Hanseatic League, Lübeck was a commercially successful and affluent city. This also meant that it was a target for rivals, and needed protection from attack. Protection was built in the form of solid city walls with gates, and a moat around the city. A dialectic emerges here: the enclosure and constraint of a settlement that wants to expand and prosper. Lübeck’s passageways were one response to this: a “thickening” of the urban fabric, in which new abodes were built cheek-by-jowl with others, creating intricately layered spaces with high population densities.

In the fourteenth century, as space became a premium in the city, enterprising merchants built shacks in the backyards of their properties, and rented them out to servants, labourers and seafarers. In one sense then there is a similarity with the nineteenth-century tenements of German towns and cities, in which the affluent lived at the front of a block, and the less well-off lived at the rear.3

In Lübeck the passageways subsequently became the reserve of the city’s poorest, who suffered overcrowding in insanitary conditions. But the servants, labourers and seafarers are long gone now. Lübeck’s restored and preserved city centre is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and it is tourism now, not maritime trade, that sustains the city. In consequence, the city and its residents have transformed the alleyways of the city into the idyllic spaces that we see today.

Jonathan Meades “Magnetic North” YouTube [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dw6J9bYQ4XY]

“Dentrassis” Hitchhiker’s Wiki [https://hitchhikers.fandom.com/wiki/Dentrassis, accessed 02/07/2024]

“Hurry to see the Alleys” Lübeck und Travemünde Marketing GmbH [https://www.visit-luebeck.com/old-town/alleys-courtyards, accessed 02/07/2024]