The Church Spires of Lübeck

Did you know that Lübeck has six church spires that are over 100 metres tall? That's more than any other country in the world…

In this article I revisit a trip I made to the north German city of Lübeck in May 2024. My first article about the city’s hidden passageways can be found here.

“There is not a city of the north of Germany, which exceeds Lubeck, in the beautiful uniformity of the buildings, or the pleasantness of the groves and gardens about it.”

Thomas Nugent, The Grand Tour; Or, a Journey Through the Netherlands, Germany, Italy and France (1756) Vol. II, p.145.

In May 2024 I visited the north German city of Lübeck for the first time. I was really excited at the prospect of visiting a city that I had long wanted to explore, and I felt that, rather than follow a predetermined route, or try vainly to tick off all the places I wanted to see, I would simply let myself be led by my eyes and my own sense of curiosity. What that meant in practice was that I tended to steer away from the busier, central parts of the city, ending up in attractive sidestreets full of architectural oddities.

Lübeck’s modern history stretches all the way back to the twelfth century. Situated on the banks of the river Trave and just ten miles from the Baltic Sea, trade and commerce have played an important role in the city’s development. From the thirteenth through to the seventeenth century the city was one of the most important in the Hanseatic League. In 1226 the Holy Roman Emperor Friedrich II made Lübeck a free city of the Empire, giving the city and its inhabitants a large degree of automony from the church, and answerable only to the Emperor himself.

Lübeck’s status declined with the dissolution of the Hanseatic League in the seventeenth century. But what it increasingly lacked in commercial importance it made up for in its cultural value: a medieval city boasting some of the finest brick-built churches and houses in northern Europe.

“Lübeck is one of the most picturesque old towns in Germany, its buildings being almost entirely of brick, and deserves more attention than is usually given to it by travellers. […] It houses, distinguished by their quaint gables […] its feudal gates, its Gothic churches, and its venerable Rathaus, all speak of the period of its prosperity as an imperial free city.”

John Murray, A Hand-Book for Travellers on the Continent (1858), p.325.

Today, Lübeck still feels like a medieval city, although it did not escape the attentions of the RAF and US Air Force during the Second World War. There are plenty of post-war buildings in the city, many of which were designed with some sympathy for their surroundings. As I explored the city another thing I noted—and I tend to note this wherever I go these days, both abroad and at home—is the degree to which cars spoil our cities. I was ever thus, of course, and things weren’t really any better before their blight, when the streets were clogged with carts and horses, and their attendant dung and smell. Nevertheless, our recent predeliction for SUVs does seem to have made a tolerable situation worse.

Lübeck’s five main churches

Wherever I went in Lübeck’s historic heart, the seven spires of the city’s five largest churches loomed up above the gables and rooftops. But the fact that there were seven of them, and that they all looked very similar, did nothing to help me orient myself as I walked.

These spires dominate historic images of Lübeck. Here’s a detail from the Saints Nicholas and Victor Altarpiece by Hermen Rode. Painted between 1478 and 1481, it’s the earliest known depiction of the city and its spires, although it’s fair to say that St Victor had other things on his mind at the time.

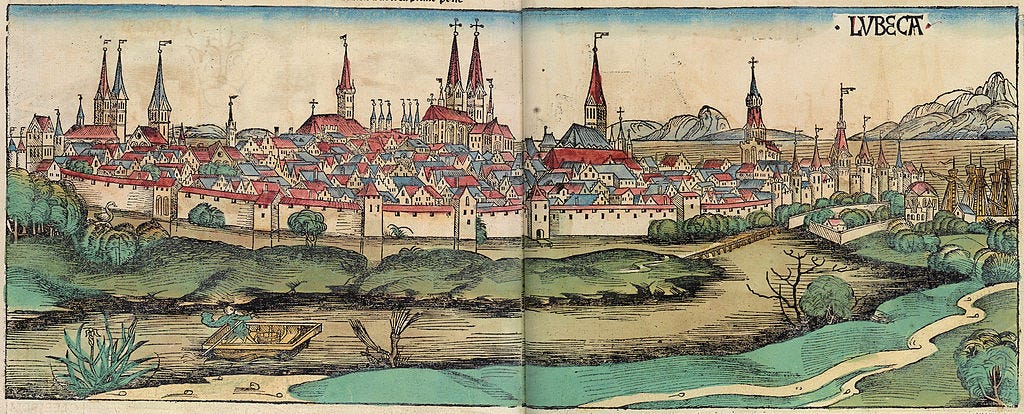

Another view of the city from the Nuremberg Chronicle, published a few years later, in 1493:

Lübeck’s five main churches are as follows:

Lübeck Cathedral (Domkirche) has twin spires, and is situated at the southern edge of the city. The cathedral was founded in 1173 by the Duke of Saxony Henry III, better known as Henry the Lion, to replace an earlier wooden church. The original cathedral, completed around 1230 was Romanesque in design, but a century later was converted into a Gothic-style building. The cathedral was largely destroyed by Allied air raids in 1942, with rebuilding commencing in 1960.

The Church of St. Mary (Marienkirche) also has two spires. Built between 1265 and 1352 on the site of an earlier church near Lübeck’s central market, its construction was funded by the city’s councillors and merchants. Like the cathedral it was built as a Romanesque basilica, before being converted into a Gothic building. Standing at Lübeck’s centre, and with the city being positioned on a hill, the Marienkirche is the most prominent of Lübeck’s churches, and the most easily seen from a distance.

The Church of St. Gille (Aegidienkirche) is the smallest of Lübeck’s five main churches, and was built by the guilds in their quarter of the city in the fourteenth century. It combines elements of Gothic, Baroque and Renaissance styles.

The Church of St Peter (Petrikirche) is the church of Lübeck’s lightermen, who manned the flat-bottomed barges that plied their trade around the city. Originally built as a Romanesque church in the thirteenth century, it was rebuilt in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries as a Gothic church. The church was destroyed in the Second World War, and its reconstruction was not finished until 1987.

The Church of St Jacob (Jakobikirche) was the church of seafarers and pilgrims, and was built in the mid-fourteenth century. It survived the Second World War unscathed.

After the arrival of the Reformation in Lübeck in 1530, all five churches became Lutheran. Of the city’s Catholic institutions, Büsching notes in his New System of Geography (1762):

The convent of Mary Magdalen in the old Burg, was at the time of the Reformation converted into a poor-house, which also has its particular chaplain and church. In the suppressed convent of St. Catherine has been founded a grammar-school of seven classes, and in this convent is also the public library. [...] The convent of St. Anne has been converted into an alms-house and house of correction, both of which are handsome buildings and under excellent regulations.

Lübeck Cathedral

Wandering around the city without a plan, I stumbled upon Lübeck’s cathedral quite by chance. It is a monumental, vertical hulk of a building, all red brick, oxidised copper-green roof and spires. It was quite unlike the Gothic cathederals of England and France, or the Catholic piles of Spain and Italy with which I was more familiar. And aside from the building, what really struck me about it was its location and aspect, quietly tucked away in a sleepy corner of the city. In most cities you find a large open square in which to stand back and admire a cathedral’s façade and architectural details. Instead, what I took to be the cathedral’s main façade overlooked a cobbled bank overgrown with grass, sloping down to a quiet side road.

Lübeck’s Rathaus, or town hall

I left the cathedral behind me and went in search of the town hall. Directly opposite it I found the Niedrigger shop, where I brought some of the city’s famous marzipan. The town hall stands at the very centre of the city, and is an imposing Gothic edifice with colossal gables and delicate spires. It was built up throughout the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, and then later embellished in the Renaissance style in the sixteenth.

The wealth of Lübeck’s merchants is just as evident inside as it is out, with its glazed-tile entrance hall and grand staircase leading to a sequence of antechambers, each divided from the next by ornate wooden carved doors, and decorated with intricate wall panelling, marble mantelpieces and fine paintings. What’s more, the town hall faces out onto an expansive market square, where it is possible to gaze up and admire the building—quite unlike the cathedral.

I sat down at one of the cafés looking out onto the market square, and ordered myself a coffee. It was late morning now, and there were a number of tourist groups congregating and milling around the square. From where I sat I could admire the town hall, and see how the nave and spires of the neighbouring Marienkirche loomed over it. This was the church that was originally built by the town’s councillors and merchants—in other words, those same men whose day jobs took them to the town hall.

“St Mary’s church is the most considerable in the place; it is a lofty edifice, standing in the midst of the city: it has a double steeple, two hundred and seventeen yards high, built in 1304; the inside of it is profusely ornamented with pillars, monuments, &c.”

Joseph Marshall, Travels through Holland, Flanders, Germany, Denmark [etc], Volume 2, 1772, p.130

It was a reminder that the spatial organisation of our towns and cities rarely happens by accident, and it should come as no surprise that Lübeck, sitting at the heart of a powerful commercial empire for several centuries, is set out the way it is. The town hall, the market square and the church built by the city’s councillors and merchants occupy the summit of a hill at the very centre of the city. But while the town hall is given precedence on the central square, I suppose it is quite right in the general hierarchy of things, in which the spiritual trumps the earthly, that the Marienkirche should loom over its commercially oriented neighbour in the way that it does.