My first encounter with Glasgow

Or, how I visited Glasgow for a day and ended up staying for two years.

I visited Glasgow for the first time in September 2006, which, when I think about it now, is so long ago now that it might as well have been in a different lifetime. I went to Glasgow to see if it would be a good place in which to study for my PhD. On paper it was a ludicrous notion: decamp from the far south of England to a city I’d never been to before in Scotland, and stay for possibly up to three years. But I was younger then. I had no ties and a sense of adventure. Anything was possible.

From experience I would suggest that if you are travelling to Glasgow, and especially if you have several hours to spare, then the best way to arrive in the city is from a long way away, and through Grand Central station. Travelling into Glasgow’s Queen Street station from Edinburgh doesn’t come close, although it perfectly befits a journey that lasts a trifling forty-five minutes. There is something to be said for arriving by car or by bus from the airport, the way you peel off the M8 at junction 19, glide down the slip road and bang, straight into the city centre. But give me a five-hour train journey and I’d take the route from London to Glasgow Central any day. (This train journey, by the by, merits its own piece at a later date).

Stepping out of Central Station’s main entrance onto Gordon Street is the traveller's equivalent of a Glasgow kiss: a bold and brash whack of big-city energy, especially if it’s wet and a late afternoon sun is shining, as it was the first time I stepped out onto Gordon Street on that September afternoon in 2006. The street might be small—little more than a taxi rank really—and flanked by the usual suspects, a newsagents and a fish and chip shop here, a branch of Greggs and a Bank of Scotland there, but it’s full of movement, of taxis waving their windscreen wipers and pedestrians wielding umbrellas; a symphony on the city’s rain-glistened cobblestones. And then you look up and get an eyeful of some off-the-scale architectural Victoriana: an array of grandiose façades embellished with decorative flourishes, hewn from red and brown stone and garnished with iron tracery, all of which screams Second City of the Empire to anyone who cares to notice.

I had an inexpensive hotel booked for the night on Renfrew Street, in the city’s Charing Cross neighbourhood. The walk only lasted ten minutes, but it took me on a tour through over a century’s worth of history. Like many British cities, Glasgow grew rapidly in the late-eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, becoming second only to London in terms of importance to Britain’s overseas empire. An army of labourers built gargantuan ships in the sprawling dockyards on the river Clyde, and stoked the iron furnaces that glowed day and night in the city’s industrial neighbourhoods. Yet more labourers facilitated the flow of goods in and out of warehouses in the merchants’ quarter. Meanwhile in the city centre, bankers and capitalists counted their wealth in ostentiatious office blocks, just like those in and around Gordon Street.

As the city grew a gridiron pattern of streets emerged, north of the river Clyde, between the cathedral to the east and Blythswood Hill to the west. The gridiron layout of the city centre means that Glasgow more closely resembles American counterparts such as New York and Chicago than other UK cities. So much so that filmmakers frequently use these streets as a stand-in for Manhattan. In recent years central Glasgow has become 1960s New York for the fifth instalment of the Indiana Jones franchise, and Gotham City for DC Comics’ The Flash. I had not yet been to New York when I first arrived in Glasgow, but I’d seen enough feature films to know that the city felt distinctly American. All that were missing were the yellow taxis and fire hydrants. And as I walked to my hotel I fell in love with Glasgow instantly. The way that every street intersection opened up another vista, left and right. Those long straight streets striking out into the distance, lined with a heady mix of old and new buildings and bristling with traffic.

By chance I’d picked a place to stay overnight that was in one of the more intriguing spots in the city. My hotel stood at the very end of Renfrew Street, at the edge of the gridiron city centre, and within earshot of the M8 motorway. The M8 is arguably Glasgow’s most contentious feature. Unlike most motorways which tend to bypass city centres, the M8 carves Glasgow in two, creating an artificial boundary through the middle of the city.

In 1945 the Glasgow Corporation published a report by its lead engineer Robert Bruce, outlining recommendations for the city’s future development. In the report Bruce recommended that huge swathes of the inner city be demolished and redeveloped; an almost Corbusian vision that recommended the demolition of numerous important buildings including Glasgow Central Station, the Glasgow School of Art, and the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum. These landmarks would ultimately survive, but Bruce’s proposal to drive a motorway through the middle of the city, demolishing whatever lay in its path, was passed.

Between 1968 and 1972 construction workers cleared a large stretch of Glasgow’s historic urban fabric, cutting through neighbourhoods including Charing Cross and Anderston, to make way for the new motorway’s elevated sections, underpasses and slip roads. After this inner city section of the M8 had been completed Glasgow was divided in two, with the city centre and the West End becoming separate entities.

It’s hard to think of another UK city that has been so transformed in the postwar period by such “creative destruction”1 under the guise of urban planning; by the construction of the M8 motorway, and the relocation of its population from inner-city Victorian slums into new high-rise blocks on the outskirts of the city. And now, in recent years, some of these processes have started to reverse, and it is the postwar high-rise blocks that are being demolished, and the inner-city neighbourhoods that are being renewed.

There is also significant momentum to reverse the damage caused by the construction of the M8, and there are many in Glasgow, such as the Replace the M8 pressure group, who argue that the benefits of closing this destructive section of the motorway running through the city centre—to the economy, to tourism, and the city’s own traffic flows—outweigh the costs.2

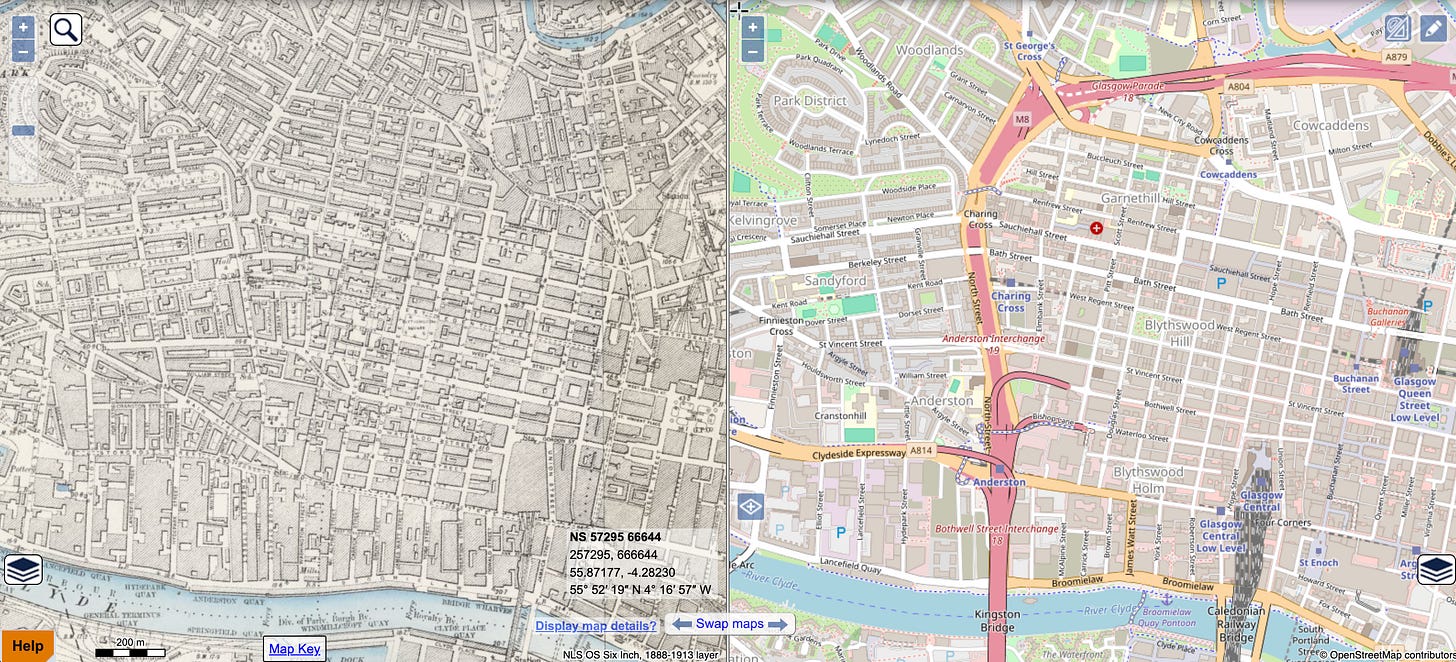

Pre-war maps give a sense of what was lost when the M8 was built through the middle of Glasgow. The motorway follows the path of North Street through the city centre, the eastern side of which was demolished for the motorway’s construction. St Matthew’s United Evangelical Church on Bath Street was one victim, as was the headquarters of the St Andrews Ambulance Association, which had only been built in the 1920s. The North Street burial ground, opened in 1821, was also lost to the motorway, its contents disinterred and moved to another graveyard.3

Another loss was the Gaiety Theatre on Argyll Street. The Beatles played there in 1963, just two years before its demolition. Anderston Cross, one of those Glaswegian tenement districts that city planners regarded as slums, was largely razed to make way for the new motorway. On Piccadilly Street St Mark’s Parish Church, an adjacent burial ground, and a Roman Catholic school were all bulldozed to make way for the motorway.

These places only exist now in historic records; in yellowing Ordnance Survey maps and faded sepia photographs4, as entries in the ledgers and journals kept in Glasgow’s Mitchell Library, and in the fragments of personal recollections that have been preserved on community websites and Facebook groups, often by luck more than design.

Peopled places have become empty. They now exist as hollowed-out liminal spaces in and around and sometimes under the M8 motorway. For example Argyll Street was once one of the city’s most important arteries, connecting Central Station in the city to Kelvingrove in the west end. The motorway truncated the street’s western limb, which now ends in an abandoned cul-de-sac, that in turn dissolves into a series of pedestrian paths, one of which leads to a footbridge over the motorway.

The hotel in which I stayed that night in September 2006, the Charing Cross Hotel on Renfrew Street, narrowly escaped demolition when the M8 was built. It was once part of a longer terrace but now it stands at the very end of the street, with just a small patch of green separating it from the dual carriageways and slip roads of the motorway. Early twentieth-century maps of the area clearly indicate buildings adjacent to the hotel, with the road and the buildings curving round and connecting up with Buccleuch Street, immediately to the north.

After my dinner I took a walk around the streets adjacent to the hotel, curious about where I was staying. The area to the south of Renfrew Street, where the eastern side of North Street was demolished to make way for the motorway, is very different in character to the rest of the city centre. Whereas the city centre is a mix of old and new in which old red and brown stone buildings continue to predominate, the western edge of the gridiron centre is overwhelmingly modern. Overlooking the hotel there are brick-built post-war office blocks, brutalist skyscrapers, and glass and steel boxes housing yet more offices and hotels.

Behind these skyscrapers are more dissonant spaces where old Glasgow meets new: a petrol station and a concrete multi-storey car park, directly across the road from the offices of the Scottish Opera, which is housed in the former headquarters of the Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders, built 1907, and a Quaker meeting house, formerly home to the Royal Artillery Club, and built in the 1860s.

The daylight was fading fast as I wandered about these strange urban spaces, which added an extra layer of otherworldliness to the scene, and I had just enough time before the light disappeared altogether to loop around and cross Sauchiehall Street to check out Charles Renne Mackintosh’s Glasgow School of Art, before turning in for the night.

I’d only been in Glasgow for a few hours, but I knew instinctively that it was a city I wanted to spend more time in. So when I switched off the bedside lamp in my hotel room that night, I’d already made up my mind: I was going to move to Glasgow. I was going to live here to study for my PhD.

A phrase popularised by the Marxist geographer David Harvey in work such as The Urbanization of Capital (1985).

Russell Leadbetter, “M8 in Glasgow: Should it be scrapped?” The Herald, 16 April 2023 [https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/23453466.m8-glasgow-scrapped/, accessed 1/11/2024]

“Lost Graveyards – North Street, Anderston” Glasgow & West of Scotland Family History Society, 2020 [https://www.gwsfhs.org.uk/2020/10/24/lost-graveyards-north-street-anderston/, accessed 30/10/2024]

There are lots of great photographs to view at the Mitchell Library’s Virtual Glasgow online exhibition: https://www.mitchelllibrary.org/virtualmitchell/home?WINID=1730267813556

Same here, Glasgow takes you in if you like cities Its an amazing place