My first encounter with Berlin

Sometimes visiting a new city can alter the course of your life.

Following on from my account of my first encounter with Glasgow, I’d thought I’d share another first encounter: this time with Berlin. I published a shorter version of this many years ago on my old Wordpress blog.

I nearly didn’t make my first planned trip to Berlin, in February 2005. And I’ve often wondered: if I hadn’t made it, how different would my life be from what it is now? I was struck down by a debilitating dose of flu two weeks before I was due to fly out, and I’d spent most of those two weeks in bed, only considering myself fit to fly a day before check-in. I had endured restless, sleepless nights of anguish during my illness, and on at least one occasion I had been so feverish that I had suffered hallucinations, waking in the middle of the night, drenched in sweat and shaking uncontrollably under my duvet, convinced that there was a metal corkscrew-like contraption within my chest, slowly expanding as it unwound itself, threatening to rip me asunder. I lay there, tossing, turning, and unable to think coherently, and it took a great deal of effort for me to realise that all I needed to do was reach over to my bedside table for the paracetamol that would help me regain control over my frenzied mental state.

On the day prior to my departure, after having awoken from the first deep and untroubled sleep in a fortnight, I felt confident enough to make a trip that I had begun to seriously entertain thoughts of having to forgo. I expect that, had I consulted a doctor on the issue, he or she would have sternly advised me against any such excursion, coming as it did so swiftly after a debilitating illness. And they would probably have been right, because I felt extremely frail and tired during my first trip to Berlin.

My trip was a week-long study visit, organised as part of the art history Master’s degree I was studying for. There were about fifteen of us students in all, and our tutors had arranged visits to a number of places including the Old and New National Galleries, the Berlinische Galerie, the modern art museum in the Hamburger Bahnhof, and the Bauhaus Archive. When I wasn’t studying for my Masters I worked as a freelance graphic designer, a job for which I’d lost all enthusiasm and what little talent I’d started out with. I hated freelancing, with its long hours and a standard of living hovering somewhere around the poverty line that it invariably seemed to entail. I rarely travelled abroad in those days, so I was very excited about the prospect of visiting Berlin – and Germany – for the first time.

About a month before we travelled out, Dirk Hansen, a lecturer in architectural history from the University of Plymouth and a native German, came to talk to us students about Berlin and its history. ‘Berlin is a very boring city now’ he lamented, ‘it was a far more interesting place before the Wall came down.’ He was probably right, and his words have stayed with me.

I and three of my colleagues travelled on the same flight from Bristol to Berlin, arriving after dark at the city’s Schönefeld Airport. Schönefeld had been the main terminal for Communist East Berlin, but had become almost exclusively the domain of EasyJet flights, with nearly every bare surface painted a lurid orange. A brutally cold winter’s evening confronted us as we stepped out from the arrivals lounge. On such a cold night, with no experience of Berlin’s transport system, and barely a word of German between us, we opted to take a taxi to our hotel, which was located in the city’s west end.

From the warmth and comfort of the front passenger seat of our taxi – a beige Mercedes, like all official city taxis – I watched the southern suburbs of Berlin slide by under cover of darkness. We sat in silence as we travelled. Our driver was not the talkative type and happily kept the volume of his radio low, leaving us to our own thoughts and the sight of unfamiliar nocturnal streets quietly slipping by. What I saw was a mix of bright-lit arterial road intersections, modern apartment blocks, advertising hoardings, car lots, shop windows and fast food joints. An uncanny vision, comprising all those constituent parts of suburban life with which I was entirely familiar, yet all subtly different enough in their smaller details so as to produce a decisively alien impression. I had no idea how long the journey would take, and the blue street signs indicating the lanes and turn offs for different neighbourhoods of the city were of no use to me in ascertaining our progress: Buckow, Marienfelde, Steglitz, Schmargendorf, Friedenau… After about forty minutes’ drive we arrived at the front of an unassuming hotel on a quiet street, nestled behind the bright lights of the Kurfürstendamm and Wittenbergplatz. When I stepped out onto the street pavement of Berlin for the first time, I did so through the satisfying crunch of a thin layer of snow.

I did not see a great deal of Berlin during that first, week-long visit. In fact, given that we visited in mid-February, and that the weather remained at best murky and dull throughout the entire week, I probably saw only three or four hours of daylight each day, most of which were spent inside museums and galleries. And yet I would counter that my fragile state, which existed in both a corporeal and an emotional sense, allowed me to experience what I did see of Berlin in a profoundly raw and powerful manner. I felt like the storyteller of Edgar Allen Poe’s Man of the Crowd, who, while convalescing from his own debilitating illness, sat in the window of a London coffee shop with his cigar and newspaper, and watched the crowds milling past outside. Poe’s narrator acknowledged the strength that was slowly returning to him, and the joy of his recovery filled him with an unparalleled keenness and inquisitiveness, an interest in all the things in life, a genuine joie de vivre. On that night of our arrival on a cold February evening, as we travelled by taxi from the airport to the hotel, I myself felt a sense of joy akin to that which Poe had described. The darkly lit streets, with their apartment blocks, signs, and advertising hoardings, might have been alien to me, but their unfamiliarity filled me once more with a simple fervour for living.

The hotel in which we were staying was situated on Fuggerstrasse, which was a fairly typical Berlin inner-city street. I’d been expecting narrow streets bursting with colour, noise, people and traffic, but instead I was confronted with a near-deserted tree-lined avenue, as wide as it was quiet, and home to a mix of sleepy restaurants, residential blocks and shops whose shutters had long since been rolled down for the night. But I have learnt that superficial impressions such as these, and especially in the case of Berlin, should be treated with due deference, and by the end of the week my impressions of Fuggerstrasse had indeed changed, not least because of the many male couples that I saw, arm-in-arm or hand-in-hand, pointing me towards the fact that this neighbourhood was an integral part of West Berlin’s gay community.

According to our trip’s itinerary, we were to spend the morning of our first full day in Berlin exploring the Neue Nationalgalerie, the city’s principal gallery of international modern art, and Mies van der Rohe’s most distinguished contribution to the Berlin cityscape. At breakfast my colleagues and I consulted our street maps and city guides, plotting the best route from our hotel to the Kulturforum, the collection of post-war cultural institutions built by the West German government in the sixties, amongst which can be found Han Scharoun’s philharmonic hall and state library buildings, and the Neue Nationalgalerie. Most of my colleagues opted for the warmer, quicker and more comfortable option of travelling on the U2 underground line from Wittenbergplatz to Potsdamer Platz, but a handful of us decided to be more adventurous and make the journey on foot. The route was straightforward; all we had to do was follow the main road north, up to the Landwehrkanal, and then follow the canal itself east towards Potsdamer Platz.

When we left the hotel we found that a modest amount of snow had fallen overnight, leaving the pavements and rooftops with an icing-sugar finish. The temperature, at a guess, remained several degrees below zero. At the end of our street we turned left onto the An der Urania, one of those typically ugly post-war urban thoroughfares that Berlin has plenty of, and which make no effort to endear themselves to pedestrians, lumbered as they are with unremarkable office blocks and bland corporate chain hotels. As we walked we passed the ground-floor windows of several hotels, where we saw groups of American and Japanese tourists enjoying their continental buffet breakfasts. When we crossed the Landwehrkanal and turned right into Von-der-Heydt-Strasse, the character of the streets changed dramatically, with many more pre-war buildings intermingling with modern counterparts. The road along which we now walked was far more peaceful than the dual carriageway we had just left, and with the canal to our right and the snow muffling our footsteps, an overwhelming sense of tranquillity prevailed. I discovered later that this part of Berlin, bordered by the canal to the south and the Tiergarten to the north, was—and remains—Berlin's embassy quarter, being home to a diverse range of consulates from around the world. During the Second World War, many of these embassies were badly damaged by bombs, and it has been only since German reunification—and Berlin’s renewed importance as capital of a reunified Germany—that many nations had begun the process of building themselves new consulates in this area. The street opposite the canal was evidence of this change: a mix of grass-covered empty plots, construction sites, and immaculate, newly built embassies.

After a few minutes walking we came to a street branching off to our left called Hiroshimastraße. At the end of this street, just a couple of hundred yards ahead of us, we could see the bare trees of the Tiergarten. What really demanded our attention though was the diverse array of buildings lining each side of the street. With time on our side, we ventured down Hiroshimastraße to explore further.

What we saw as we continued down the street has stayed with me ever since, and it would be no overstatement to suggest that my fascination with Berlin began at that very moment. Immediately on our right stood the Friedrich-Ebert archive, a modest and quite impressive new construction, dominated by large windows and purple brickwork. A little further down on our left, we saw the faintly ridiculous embassy of the United Arab Emirates, a new, gaudy construction which, I recall remarking to my colleagues, looked like the sort of thing Disney might come up with if they ever got into the embassy-building business. Alongside this embassy stood the regional administrative offices of the North Rhine and Westphalen regions, a vast transparent box, behind whose glass walls we could see an intricate framework of wooden gothic arches.

On the opposite side of the road stood a pre-war building, a ruin, whose cracked and derelict appearance amid overgrown flora, barricaded behind metal fencing, hit us like a shock. The stone neo-classical façade betrayed significant structural damage, with one particularly large crack visible in the stone arch above the door, and all of the windows boarded up. On each side of the building lay derelict and overgrown open ground. This open land allowed us to see down the complete length of the building, which extended back along the entire depth of the block. From our position we could discern rooms and stairwells, all exposed to the elements. On the bare exterior walls were the marks of adjoining but long-gone buildings, presumably destroyed outright in the war; of floor levels, stairs and fireplaces.

This contrast between the old and the new, between decay and redevelopment, struck me as utterly fascinating, and as I stood there that morning in the bitter cold, still weak from my bout of flu, the experience cut deep into my imagination. There is a school of thought in physics that argues that the past, present and future all coexist together, and it seems to me that few cities encapsulate this idea better than Berlin, where it is possible – as it was then on Hiroshimastraße – to see the actions of the past, the status quo of the present, and the intentions of the future, all in one space.

Here it is possible to think of time not as a series of self-contained events, but as a vast current, flowing along and allowing past, present and future to commingle with and influence each other in ways I had hitherto thought not possible. I realised that here in Berlin, the past, present and future collided with each other more dramatically than in any other city I had visited. Nowhere was this fact so brutally inscribed than in the city’s streets and buildings.

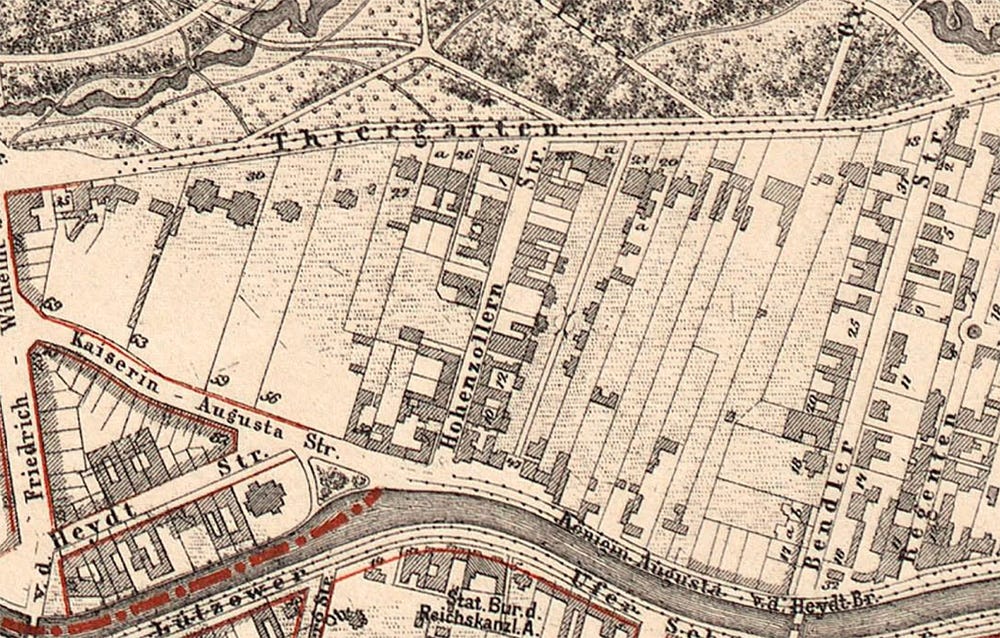

Much later on I learnt that, unsurprisingly, Hiroshimastraße was a relatively recent name. The street was created in 1862, as part of urban planner James Hobrecht’s plans for the expansion of Berlin. The city authorities named the street Hohenzollernstraße in honour of the Kaiser and the imperial ruling family. When the National Socialists took control of Germany in 1933, they renamed the street Graf-Spee-Straße, in honour of the German naval commander Maximilian von Spee. Spee was a German war hero who died in the Battle of the Falkland Islands, a First World War engagement between the British and German navies which took place in the southern Atlantic on 8 December 1914. The Berlin authorities renamed the street Hiroshimastraße on 1 November 1989, just days before the Wall came down.1

Late nineteenth-century maps show us how Hohenzollernstraße quickly developed in the years that followed, to become a street lined with opulent houses owned by Berlin’s wealthy elites. The old ruin that I had seen at 11-15 Hiroshimastraße was a relative latercomer, having been built in 1911-12. It was designed by the architect Robert Leibnitz as a home for the German-American industrialist Sigmund Bergmann, former business partner of Thomas Edison, and who had established Germany’s first lightbulb manufacturing plant in the Berlin district of Wedding.

To my surprise, I also learned that the façade overlooking Hiroshimastraße was in fact one of two façades that the building boasted. On Hildebrandstraße, the next street along, it had a larger, even more impressive façade.

In 1918 the Bergmann family bought a new residence for themselves in Coburg. We might assume that they moved out of Hohenzollernstraße and Berlin in response to the political chaos then unfolding in the wake of the Germany’s defeat in the First World War. After the War a greek tobacco manufacturer acquired the building. They rented it to the Greek embassy, who moved in in 1920 and stayed until 1940.2 Aerial photographs taken after the Second World War indicate the extent of the damage that the Allied bombing campaign wrought on this part of Berlin. The Greek embassy survived with minor damage, as did the Italian embassy directly to the north. But most of the Graf-Spee-Straße was destroyed, leaving empty open spaces.3

In 1948 the building’s Greek owners donated the property to the Greek government. Britain’s Military Mission occupied the building for a short while – the Tiergarten district being in the British sector of divided post-war Berlin. After that the building lay dormant for years. The Greek government had no need to use it as their embassy at this time, now that West Germany had moved its capital to Bonn. In 1983 a fire gutted the interior of the empty building, leaving it boarded up and derelict, as I had found it in 2005.

The reoccupation of the building by the Greek embassy happened very recently. Renovation began in 2017. Builders carefully removed the façade on Hildebrandstraße so that they could rebuild the interior of the property. The façade was then put back in place. Builders also contructed a new wing on the adjoining plot. Finally, in 2022, over a century after first occupying the building, Hiroshimastraße 11-15 reopened as the Greek Embassy.

“Hiroshimastraße” Wikidata [https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q1418820, accessed 08/11/2024]

“Das Botschaftsgebäude”, website of the Hellenic Republic’s embassy in Berlin [https://www.mfa.gr/germany/de/the-embassy/history/the-building.html, accessed 08/11/2024]

“Berlin 1953 und heite” Berliner Morgenpost 29 November 2016 [https://interaktiv.morgenpost.de/berlin-1953-2016/, accessed 10/11/2024]