Late nineteenth-century Berlin, and in a large room above the Kaiserpassage on the city’s bustling Friedrichstraße, a rather magical device could be found: the Kaiserpanorama. Of all imperial Berlin’s many public attractions, the Kaiserpanorama had an enduring appeal for the city’s inhabitants. The device was the brainchild of the German physicist August Fuhrmann, and was first exhibited to the public in Breslau [Wrocław] in 1880. Three years later in 1883, Fuhrmann set up one of his devices in Berlin, above the shops and cafés of the recently opened Kaiserpassage on Friedrichstraße. The longevity and charm of the Kaiserpanorama was attested by the fact that, while the fortunes of many of Berlin’s commercial amusements dwindled over time, inevitably caught up and overwhelmed in the relentless tide of invention that characterised the modern era, it continued to attract visitors right up until 1939.

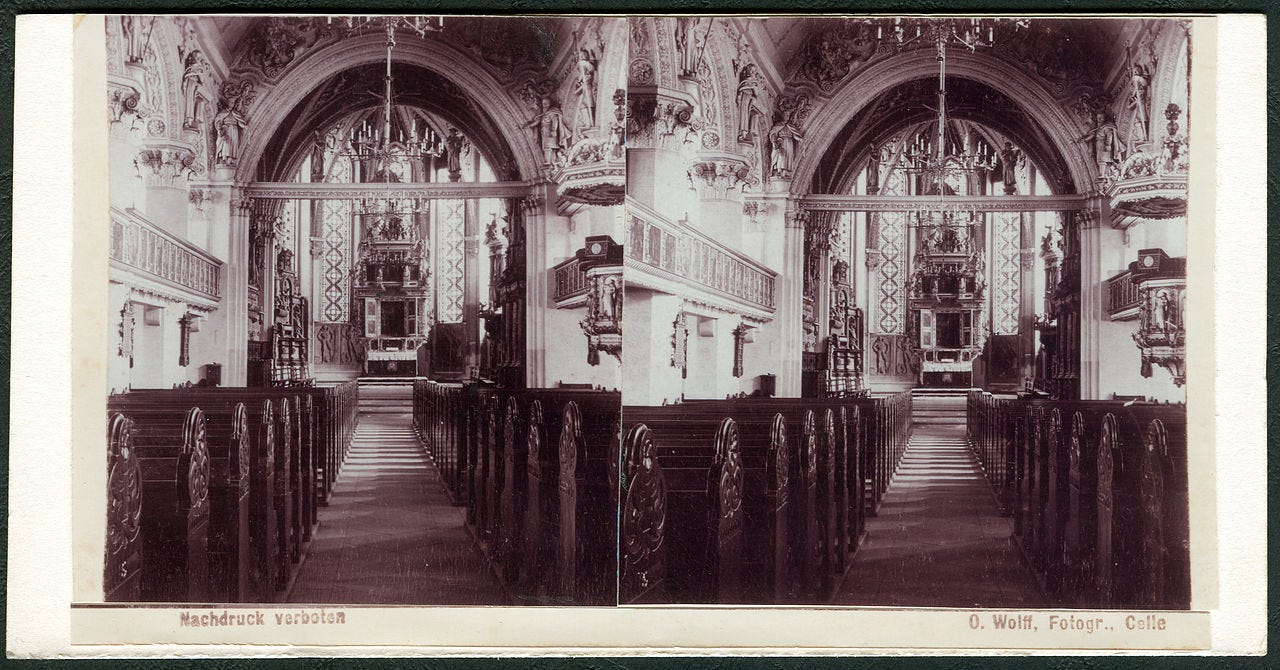

The Kaiserpanorama was not a panorama in the true sense of the term. Whereas the painted panoramas—of which there were several in imperial Berlin—enveloped their audiences and projected their image inwards, the Kaiser-Panorama inverted the spatial relationship between the viewer and the image, storing its pictures within itself, and projecting them outwards to the spectators gathered around its exterior. The Kaiserpanorama was a Victorian precursor to the View-Master stereoscopic slide viewer that millions, like myself, owned and revered as children.

I remember my View-Master vividly. Moulded from bright red plastic, it had two protruding eyepieces at the front, and a large black plastic lever on its right-hand side. On the top of the device there was a wide slot into which cardboard discs, punched with tiny holes filled with coloured acetate images, could be inserted. I remember pressing the red plastic eyepiece to my face, and being mesmerised by the images I saw. There were two discs that I recall most fondly. One displayed three-dimensional images of dinosaurs, the other scenes from the 1970s cartoon series Battle of the Planets. As I squinted through the viewfinder, my thumb seemed to have a mind of its own, seeking out and eagerly pushing down on the lever to move onto the next picture.

The Kaiserpanorama worked in the same fashion: stereoscopic images arranged around a circular, rotating device. The big difference was one of scale, and this gave the Kaiserpanorama its advantage, for while my View-Master was a solitary occupation, Fuhrmann conceived of his device as a spectacle for the masses, capable of entertaining up to twenty-five people at any one time.

Of the two or three-hundred made, few working Kaiserpanoramas survive today. One of them can be found in the Märkisches Museum in Berlin, and I saw it for myself when I first visited the museum in the summer of 2006. I had only ventured into the museum to escape a particularly heavy late-summer thunderstorm; it was barely half an hour till closing time and there were few visitors inside. As I walked along the creaking wooden floorboards of the museum’s first floor, through high-ceilinged rooms, devoid of people but filled with large hunks of period furniture, glass display cases, ostentatious chandeliers and wall hangings, I heard the Panorama long before I saw it; a soft hum reminiscent of a low-powered vacuum cleaner, interspersed with the occasional clear ding of a bell and the click-clacking of mechanical parts.

In a large and dimly lit space I encountered a huge wooden cylindrical structure, about ten feet in diameter and six feet high. As my eyes adjusted to the low light levels I could see that the circumference of the machine was divided into wooden panels, from each of which protruded a brass eyepiece. Mounted above each eyepiece was a small brass plaque, stamped with a number from one to twenty-five. Below the eyepiece there projected a small shelf that ran around the entire circumference of the machine. From the underside of that shelf hung a heavy faded green velvet curtain that reached down to the wooden floor. In front of each eyepiece stood a plain chair, inviting you to sit down, lean forward, and press your eyes against the cold brass rims of an eyepiece.

Alone in the room, I submitted to my curiosity without any hesitation. I took a seat at position number seventeen and peered into the viewfinder in front of me, and as I did so I left the present behind and found myself taken back into the world of the Kaiser and the German Empire; an artificially lit world filled with the bombast and excitement of pre-war modernity. Berlin’s Kaiserpanorama proved wildly popular, and every week, children and adults queued for a ride—as it was advertised—on its seats; twenty Pfennigs for adults, ten for children. The popularity of the device spread beyond the capital, and throughout the 1880s and 1890s,Fuhrmann sold over two hundred of his contraptions across Germany and beyond. It was rumoured that the Kaiser himself owned one, as well as the Pope and the Sultan of Turkey.

Fuhrmann was aware that, if he was to sustain the public’s appetite for his devices, he must produce a continual supply of stereoscopic images for display; no mean feat considering that Berlin’s Kaiserpanorama promised two new sets of fifty slides each week. To this end he dispatched a small army of photographers and journalists around the world, assigned with the task of photographing all manner of subjects, whether they be natural spectacles, great human achievements of engineering and science, high-profile public figures, and salient current affairs. Upon their return the photographers’ black and white films were processed, the twin images transferred to glass plates, then each one hand-painted by a team of colourists. In this manner Fuhrmann’s Kaiserpanorama opened up hitherto unknown, unseen worlds to an eager German public.

What sights would visitors to the Kaiserpanorama in turn-of-the-century Berlin have witnessed? No doubt they peered at many images of subjects with which they would have been familiar: photographs of the Kaiser and his entourage on horseback, parading past the waving crowds lining the Unter den Linden, or erstwhile politicians opening important new public buildings. Berlin figured frequently in the slides created for the Kaiserpanorama, for make no mistake, Berliners took a great deal of pride in the newness and modernity of their home city. During the era of the Kaiserpanorama’s greatest popularity, Berlin felt like a city in a perpetual state of change, and the Panorama’s stereoscopic photographs documented the ambitious construction projects taking place across the city: the colossal new cathedral rising over the Lustgarten, the Reichstag building overlooking the Spree, the soaring spire of the Kaiser-Wilhelm memorial church on the Kurfürstendamm, and the majestic Stadthaus, in the heart of the old city.

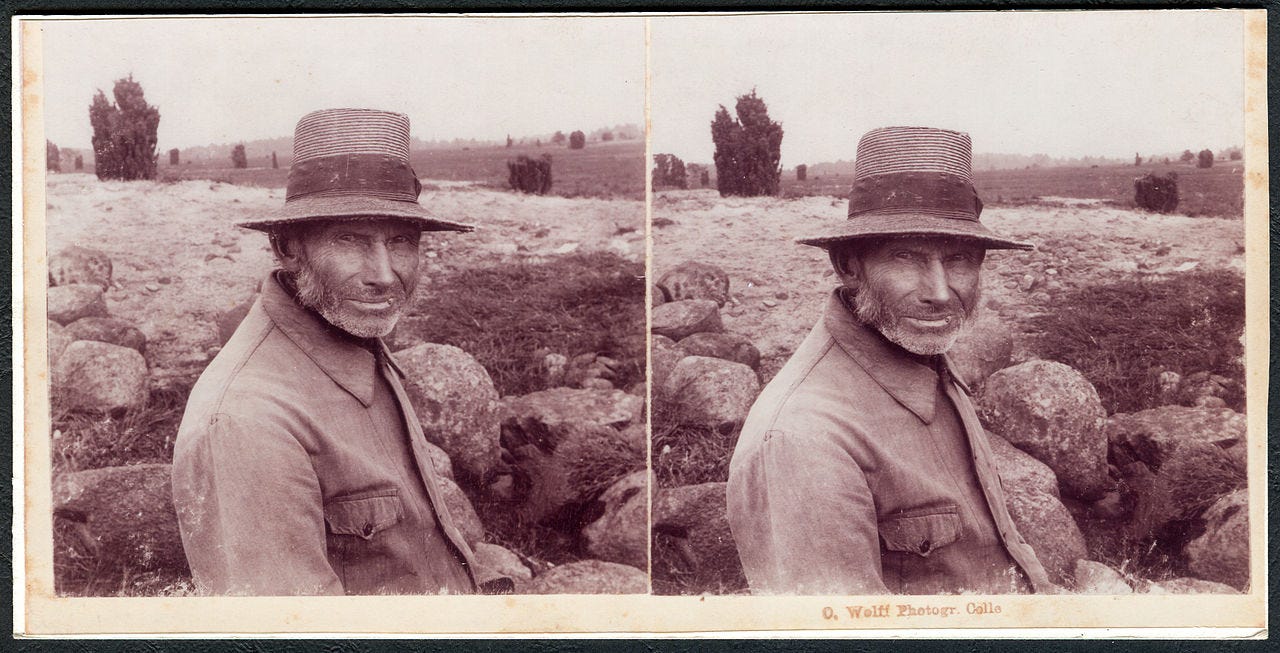

In search of images, Fuhrmann sent his reporters beyond the suburbs of rapidly expanding Berlin, and beyond the forests and fields of the Mark. Scouring the German countryside, they captured on film scenes that had barely changed for centuries. Halcyon vistas of peasants driving furrows into the black earth of the Silesian plains, under dramatic skies made all the more ominous by the colourist’s paintbrush; scenes depicting row upon row of grape vines clinging to the steep slopes of the Thuringian hills, overlooking exquisite villages with their charming church spires and steeply gabled roofs; panoramic views of fishing boats negotiating sandbanks off the coast of East Frisia, their sails billowing and their nets cast under bleak North Sea skies; scenes of dramatic mountainous vistas from the Black Forest, enveloped in mist and caught in glimpses through the gaps between dark tree trunks; and finally, images of fairytale-like castles perched atop craggy precipices.

Fuhrmann’s photographers travelled further, beyond Europe, crossing the world’s oceans to reach far-flung places, dragging trunks filled with their camera equipment behind them. Max Brod wrote of finding himself in Florence, and then travelling to the city of Bitlis, capital of Kurdistan, and onwards to Ceylon. Hans Adler wrote of seeing Vesuvius, Niagara Falls, the Pyramid of Cheops and Lima.1 Not unsurprisingly, Fuhrmann frequently dispatched his reporters to Africa, where Europe’s colonial superpowers—including Germany—were fighting over the last scraps of territory on the vast continent. They sent back photographs from Cameroon, showing the indigenous peoples, scantily dressed in their traditional garments and holding their spears and tools, standing proudly outside of immaculately constructed huts of mud and straw. Then the reporters—doubtless guided by their German hosts—took photographs of the natives idling in the heat under the shade of the trees, and then followed these images up with scenes of the natives organised into makeshift police units, equipped with rifles and marching in columns, while their German occupiers looking on approvingly from the sidelines.

Yet more photographs celebrated the newest inventions of the era, and it was pictures such as these that I saw for myself in the Kaiserpanorama in the Märkisches Museum. How might the man on the street have responded to three-dimensional photographs of the Zeppelin LZ1, pictured floating above Lake Constance in southern Germany, or the Wright Brothers’ flying machines, frozen in time and space by the camera, hovering impossibly just inches above the ground, in a state of either having just taken off or being just about to land. And then there were sequences of photographs showing the latest building developments around Wall Street and Manhattan in New York, with their soaring skyscrapers, far taller, far more impressive, than anything the German capital could boast.

By the turn of the century photographs of the German navy had become a recurring theme. Viewers frequently saw images of colossal ships like the Blücher of 1890, and the formidable dreadnoughts of the early 1900s. Awestruck at the scale of such engineering achievements, they marvelled at photographs of these great vessels under construction at Kiel and Wilhelmshaven, in which dockworkers clambered about like ants over monstrously sized anchors and propellers. The Kaiserpanorama also presented these great ships at sea, taking part in naval exercises in the North and Baltic seas, no doubt inspiring the German public that, should England declare war on Germany, the Fatherland would be able to defend herself. And in 1914, when war finally did come, Fuhrmann’s devices were recruited as a propaganda tool by the authorities. As the situation on the western front became increasingly bloody, bleak and deadlocked, the inhabitants of Berlin saw sanitised stereoscopic images of dry, clean and orderly trenches, occupied by impeccably dressed and well-drilled German soldiers.

After the First World War, Berlin’s Kaiserpanorama—hidden away in its dark room above the Kaiserpassage on Friedrichstraße—continued to attract visitors, albeit in dwindling numbers. The moving images projected onto the screens in the cinema theatres were capturing the imagination of the public now. And there must have been something dreadfully anachronistic about a device whose name alone associated it with an exiled figurehead and a banished era. And yet the Kaiserpanorama laboured on, surviving even the closure of the last attractions in the neighbouring panopticon, the radical redesign of the Passage below, and the dramatic economic upheavals and political strife of the early thirties. It wasn’t until 1939 that the doors finally closed upon Berlin’s Kaiserpanorama. But by then, one suspects, Berlin’s public had far more pressing matters on their minds.

I remember how intrigued I was, when I first encountered the Kaiserpanorama in the Märkisches Museum, at the way in which the device regimented time so methodically. Each of the fifty photographs slid into view and remained before the eyes for just a short period of time before sliding past, and then, inevitably, the first image I had seen would eventually reappear once more. The mechanical regularity of the process of viewing—knowing that each image only appeared for a short space of time—did not so much increase the sense of anticipation for the next image, as heighten the feeling of regret at having to take leave of the present one. This anguish was further intensified by the bell that rang to announce the imposition of each new image, which occurred seconds later, a bell that, as Walter Benjamin remembered, had a ‘small, genuinely disturbing effect’ on him as a child, and which he considered as being superior to the ‘soporific’ music that soundtracked the moving images he later saw on the cinema screen.2

The sense of melancholy the Kaiserpanorama was capable of inducing, provoked by the acute awareness of time passing and images (and memories) lost, was, I think, what made the device so compelling, and what allowed it to endure in its darkened room above the Kaiserpassage in Berlin for so long. This unique quality, that neither the printed photograph nor the moving image on the cinema screen was capable of reproducing, was also what compelled both Benjamin and Adler to re-imagine the Panorama later on in life, from individual standpoints scarred by exile, tragedy and loss.

To them, the Kaiserpanorama represented not simply the innocent idyll of childhood—young Josef’s visits with his Grandmother, the young Benjamin stopping by before going home to finish his schoolwork—but an innocence latent within the ambitions and aspirations of the Kaiser’s Germany, ambitions and aspirations darkened by the tragedy of subsequent historical events.

Hans Adler, Panorama (New York: The Modern Library, 2012), p.4.

Walter Benjamin, Berlin Childhood around 1900 (Harvard University Press, 2006), pp.42-44.